Music & Beyond: Thereminist, Author & Orchestra Captivate a Congregation

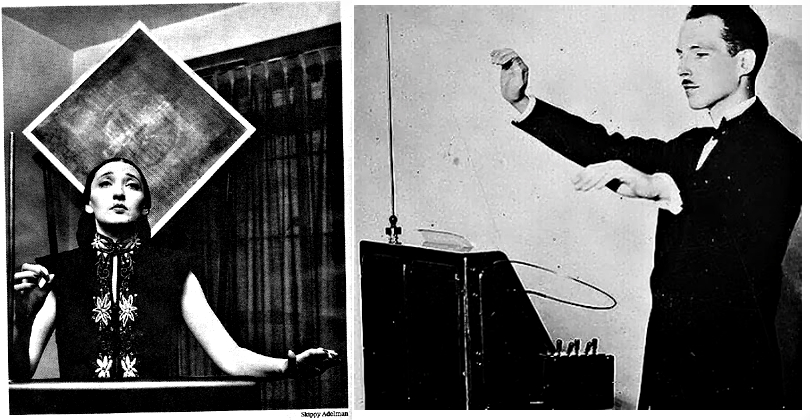

[Editor’s Note: researcher, writer & correspondent Lital Khaikin has always known there was a special place in her heart for the theremin. “Music & Literature” took place Tuesday, July 14, at Southminster United Church as part of Music & Beyond with a small orchestra, Sean Michaels reading from his novel Us Conductors and thereminist Thorwald Jørgensen making music out of thin air.]

“Après tous, le coeur est le conducteur.” – Us Conductors, Sean Michaels

[I.]

First piece performed for the night is Spellbound Concerto by Hungarian composer Miklós Rósza, scored for Alfred Hitchcock’s film Spellbound. Ottawa-raised, Montreal-based writer Sean Michaels reads from his 2014 Giller Prize-winning novel, Us Conductors, a fictionalized account of the relationship between inventor of the theremin, Léon Theremin, and the legendary Lithuanian-born thereminist Clara Rockmore. Michaels refers to the significance of Spellbound Concerto as a turning point for the public perception of the theremin as a novelty, when the instrument would become recognized more as a parody of eerie science fiction effects, rather than taken seriously as a concert instrument.

Classical compositions that have been interpreted for the theremin are romantic and melancholy, pulling from the work of Dvořák and Ravel, Chopin and Rachmaninoff. But the potential for the instrument is great, especially as a conduit for avant-garde composition. In 1966, John Cage collaborated with American dancer Merce Cunningham and Korean-American video artist Nam June Paik in Variations V, an interpretation Theremin’s related invention of the terpistone (1932), where sound was controlled by the movement of dancers. Alvin Lucier experimented with a similar instrumental process in his “Music on a Long Thin Wire”, which similarly relied on magnetism.

Contemporary composers and performers of the theremin are challenged to reinvigorate audiences with a reverence for the ethereal qualities of the instrument. Dutch musician Thorwald Jørgensen led a programme that featured compositions that have become acclaimed for the theremin, since the instrument’s invention in the Soviet Union less than a century ago.

Introducing the theremin, Michaels refers to its sound as alien to the earth, but this is untrue to the vastly unexplored potential of sound that is in fact native to our earth. The instrument responds to changes in the electromagnetic field, where the body’s presence alters the sound frequencies by drawing closer or farther. Jørgensen’s theremin has two metal rods that control pitch and volume based on the proximity of the hand. What emerges is a startling aria, near-human and utterly ethereal.

[II.]

In a moment of perfect serendipity, the melancholy of the violins and cello, in all the warmth of their polished wood and strings, were in complete unison with the rain beginning outside and the voice of the theremin that was just as present and invisible. The musicians begin Pastorale by Anis Fuleihan of Cypriot, Cyprus.

Only then, after the anticipation for the first meeting with our new instrument had passed, did it became possible to hear the theremin as it is in the company of others, discerning between the individual voices with more attention and clarity. This contrast had been forming as a vague sense from the first uttering of the theremin, but with a slower, quieter pace this difference becomes more prominent.

The aerial nature of this instrument that, minutes before, seemed to complete a chorus, now reveals an uncanny power to make all accompanying string instruments sound grotesquely artificial. Violin, viola and cello, piano, and oboe all seem sharp and empty, lacking the depth that at once encompasses and emanates from the theremin’s tone. In this imbalance it’s as though not all is as it should be, and this unordinary sensation is disturbing.

This is not only an exciting demonstration of the powerful transformation of a perceived tone through the relationships between different instruments, but of sound from a single instrument overpowering as a spatial experience.

[III.]

With the performance of Fantasia by Czech composer Bohuslav Martinů it is difficult to ignore the physical force that is required to play other instruments. The grace of the violin player is transformed into a brute grating, each musician suddenly more of the body that presses, pushes and grates against an instrument, than an illusory tempter of sound. The hammering piano and the forceful breath of the oboeist become all the more apparent, all the more pathetic in their constant straining.

The diminished presence of the other instruments allow for the theremin to truly dominate for the first time. Only when the instrument is isolated in this way is it possible to hear a richness and depth that, when in the accompaniment of other instruments, is lost in the collective sound. This depth is contributed by the glissando of the theremin, where instead of a punctuation of individual notes, the pitch is changed through a continuous, persistent stream of resonance.

It is also the first time that becomes possible to hear the deeper frequencies possible through the theremin. Such a full and heavy bass reaches to depths beyond possibilities of the orchestral instruments, reminding of the magnitude and extent of sonic frequencies that are natural to our cosmos, the grandeur of such sound extending far beyond wooden, brass and fleshly bodies. As music of the theremin is less created through the instrument, and more conjured from the electromagnetic field that surrounds the metal rods, it indicates that sound as always present, and is always multidimensional. The nature of the theremin allows a musician to reveal sound, and perhaps even approach a music that transcends materiality.

Canadian pianist Glenn Gould, when speaking of German expressionist composer Arthur Schönberg, referred to the “significance of gesture” as opposed to “the seductive lustre of attractive sound”*. The imprint of the instrument and the musician’s body would be forgone in favour of an ideal. A music that is revealed would be removed from the colouring of artifice. The theremin is exactly this: uncoloured by embellishment, provoked through gesture, not touch, an instrument of the intangible, of ideas, of air.

* Geoffrey Payzant, Glenn Gould: Music and Mind. (Toronto: Prospero Books, 2008) p. 46.

[IV.]

The theremin assumes its wordless voice in Vocalise by Sergei Rachmaninoff. Vocalise is written as a vocal exercise, to be sung as a single vowel by a soprano or a tenor, making it all the more enchanting to hear it sung by currents of electricity.

Sirenum scopuli, a composition by Canadian musician Victor Herbiet follows, interpreting the Greek myth of the Sirens. The deadly and alluring melody is carried by a meeting of theremin and harp, as though two ethers were conversing. Yet, one is rooted in the changeability of its material – the wood, the strings, the earthliness of touch – while the other is invariable under the weightless gesture that never finds grounding.

Through the Ethereal Gate, a composition for the saxophone and theremin, requires Herbiet to change over from Jørgensen’s theremin to a variation that has only a single metal arm to control volume. The inability to modify pitch results in a unitary tone that is somehow less than its more volatile counterpart. Yet, it matches in perfection, as there is no fundamental difference in the pure, electromagnetic force the instrument translates. Herbiet accentuates the anxiety of the saxophone by relying on that more eerie quality for which the theremin has become known.

[V.]

The end of the programme was brought about with “Le cygne” (“The Swan”) by Camille Saint-Saëns. Sean Michaels read a passage where the theremin was described as embodying a sense of mortality. Such a sense of mortality may be written into the composition, but is it possible for the theremin to express decay?

Written for the cello, the composition expresses the tragic myth of the swan that sings only once in its life, before death. This is perhaps the closest we may come to giving the sound of the theremin some earthly comparison, but even then, there is no conclusive sense to the theremin’s tone that could equate the urgency of relinquishing life. No, this instrument speaks with a different voice, that may speak of mortality but which cannot resonate with the same break in its voice as one that knows this imminence. The glissando that carries the theremin’s voice gives it an impossible permanence. In its clarity and unwavering breadth, there is an unsurmountable coldness of a sound that knows no death.